- Home

- Linda Fairstein

Likely To Die Page 8

Likely To Die Read online

Page 8

She got off the elevator on six as I continued up to the eighth floor, where my office had been since I took over the Sex Crimes Prosecution Unit. It was across the main hallway from Battaglia’s suite and on the corridor with other executives of the Trial Division who supervised the thousands of street crime cases police officers brought to our doorstep every single day and night of the year.

I turned on the light in my secretary’s cubicle, the anteroom to my office, and unlocked my door. My space was neater than usual as I glanced around, which pleased me. I knew how cluttered it would soon become with the reams of paperwork, police reports, diagrams, notes, and news clips that were the staples of a major investigation. I liked to start out with a spot of visible green blotter under the piles of case reports so that I didn’t lose control of any matter that required action or attention.

My first call was to David Mitchell’s office.

He had read the morning papers and knew that I was assigned to the Mid-Manhattan case, “I would never have left the note about Zac last night if I had known you would be this busy. I’m sorry to have bothered you.”

“Are you kidding? It will be a pleasure to have her to come home to, David. Plus, she may even coax me out for a jog over the weekend. You know I like her company. If I’m not home when you leave, just let her in with your key.”

“Great. I’ll walk her tomorrow morning, then take her back to your place.”

“Have time for a favor before you go?”

“Always. What do you need?”

I outlined what was going on in the medical center and explained that we wanted Maureen to be inside as an observer-unknown to administration or staff.

“Shouldn’t be too much of a problem as long as they have available beds. And as long as you’ll back me when the AMA tries to lift my license for-”

“No problem. The Police Commissioner has to approve the whole thing, so you’ll be acting at his direction once we tell him about it. And I know there are beds. Two of the homeless guys were sleeping in private rooms the past four days. For a change, no complaints about the food, either.”

“Okay, here’s what I suggest. Have Maureen call me so we can discuss some of her symptoms. Then I’ll call a neurologist I’ve done some work-”

“No, David. Dogen was a neurosurgeon. We want Mo on the neurosurgical floor.”

“Don’t worry, it is the same floor at Mid-Manhattan. The first referral would be quite naturally to a neurologist.”

“I don’t know the difference. Why don’t you start with that?”

“Of course. Neurologists are the physicians who study and treat the structure and diseases of the nervous system. A neurosurgeon wouldn’t be involved at this stage unless you’re ready to wheel Maureen into the operating room.”

“Do they work with each other, the neurologists and neurosurgeons?”

“Yes, but the neurologists can’t perform operations, they can’t do the surgery themselves.”

“Dogen did mostly brain surgery.”

“So I see from her obituary. Remember, Alex, that the brain, the spine, and even the eye are part of the central nervous system. That’s why there’s so much overlap among some of these specialties-psychiatry, ophthalmology, and orthopedics. We’ll give Mrs. Forester enough pains, tics, and twitches to keep the whole crew looking her over until I get back to town on Monday. Will that help?”

“Thanks, David. Mercer’s calling to get Mo on board and I’ll connect her to you as soon as she agrees.

“So now that I’m done with business may I ask who’s your traveling companion?”

“I’ll introduce you when we get back. Renee Simmons-she’s a sex therapist. I think you’ll really like her.”

I had the feeling that our Sunday evening60 Minutes viewing session and cocktail hour was about to expand to a threesome. “Was she the slim brunette with the perfect smile and great legs who was waiting for you at the bar at Lumi last Tuesday?” I had been on my way out the door of one of my favorite Italian restaurants one night last week when David had whipped past me on his way to claim a late reservation.

“That’s the one. Between her business and yours, you can probably mop up a few of the dysfunctionals around town.”

“I look forward to it. I’m sure I’ll speak with you again before the end of the day.”

By the time I hung up the phone and threw out the empty coffee cups, Marisa Bourgis and Catherine Dashfer had walked into the office. Both were longtime members of the unit as well as my pals. Like Sarah, they were a few years younger than I. Each was married and the mother of a toddler, and all three balanced their personal and professional lives with admirable form and boundless reserves of humor.

“So much for our plans for lunch at Forlini’s today,” Marisa said, pointing to the headline in the paper on top of my desk.

“It may be the only virtue of a high-profile case, but it’s a big one. Immediate weight loss, guaranteed.” Meals on the fly, liquid diets of coffee and soda, rattled nerves, and more running around than anybody needs in a day-stretching into weeks or months. “Perhaps a mental health shopping day at the end of all this, ladies, when I am hoping to be back to my law school size six. Takers?”

“That’s a deal. Need help with anything in the meantime? Marisa and I can help Sarah with your overflow while you get started on the murder.”

“Great offer. I’ll go through my book this morning. There may be a couple of interviews you could do for me next week. Of course, if we don’t pick up any leads by the time the weekend is over, it’ll all be in the hands of the task force, not mine.”

Laura Wilkie, my secretary of many years, peered into the room, said good morning, and told us that Phil Weinberg needed to see me before he went up to court. Urgent.

Marisa, Catherine, and I exchanged smirks as Weinberg “the whiner,” our alias for him, skulked into my office. Nothing was easy with Phil. Although he was a good lawyer and compassionate advocate, he needed more hand-holding to get through a trial than most victims ever did.

Phil was less than pleased to see that I had company. He knew we’d be talking about him the minute he left the room but he reluctantly told me the problem.

“You won’t believe what happened with one of the jurors yesterday afternoon.”

“Try me.” There was no end to the curious stories my colleagues could tell about Manhattan veniremen and -women.

“I’m in the middle of the direct case in the Tuggs trial.”

Sarah and I had spent the better part of Monday and Tuesday taking turns watching Phil in the courtroom. We did it at most proceedings with the junior members of the unit, so that we could give detailed critiques and advice about technique and style to improve the performance of these promising litigators.

I knew the facts of the case well. It was an acquaintance rape in which the victim had accepted an invitation to the defendant’s home after meeting him at a party. The twenty-three-year-old photographer was a compelling witness on her own behalf, adamant about her nonsexual reasons for choosing to go to visit Ivan Tuggs.

But this category of case still remained inherently difficult to try, despite the fact that our unit had prosecuted hundreds of them within the last ten years. It wasn’t the fault of the law but rather the general societal attitude about this kind of crime, which often made unenlightened jurors reluctant to take the issue seriously.

The basic problem faced by women who are raped by acquaintances is that the classic defense relies on painting them as either liars or lunatics. The crime never occurred and therefore the woman is fabricating the entire story. Or “something happened” between the two parties but she’s just too weird to believe.

For the prosecutor, then, more than half of the battle is in the successful selection of a jury. Intelligent citizens, who are blessed with common sense and a lot of the liberal instincts acquired by daily exposure to urban social life, handle these matters pretty well. But unsophisticated women, who tend to be far

more critical than men are of the conduct of other women, are usually better candidates for judging stranger rape cases than for assessing most dating situations. That had been my own experience too many times to count and I had tried to pass on that wisdom to my troops.

“You saw the jury, right, Alex?”

“Yes, why?”

“Well, what did you think?”

“More women than I like for this kind of case, but you told me that your panel was uneven.”

“I swear, Alex, it was a sea of women in that jury pool. There was nothing I could do about it.”

Stop whining, Phil. “What’s the problem?”

“Everything was going fine ‘til the end of the day. It was so cold in Part 82 that the jurors asked the judge to turn up the heat, just before the first cop on the scene took the stand. An hour later, it was so overheated that we were all sweating. Juror number three stood up, right in front of everybody, gave out a big ’ ‘scuse me,’ and pulled off her sweatshirt.

“What’s she got underneath? A T-shirt the size of a billboard, spread around her 44D chest, emblazoned with big fuchsia letters:FREE MIKE TYSON. ”

It was hard to stifle my laugh, but Marisa and Catherine were ahead of me.

“It’s not funny, guys, really. Tyson was tried in, what, ‘91? That means this woman hasn’t bought a lousy T-shirt in more than half a dozen years and had no choice but to wear this one, or else she sincerely believes in her cause. And if that’s the case, I think we’re screwed.”

“What did the judge say?” Marisa asked.

“Well, nothing. We just kind of exchanged glances, but-”

“You mean you didn’t ask her to examine the juror in chambers? Get your ass up there immediately, Phil. I heard the part of your voir dire when you questioned them about whether they believed the nature of the relationship between the parties made this a ‘personal matter’ and not a crime. You got all the right answers.

“You’re in front of a really good judge for issues like these. Tell her you want a sidebar and that you’d like her to ask number three some questions before you get under way today.”

“Don’t you thinkI should be the one to ask them?”

“No way. We’ll give them to you now, and you write them out for the judge. The last thing you want the juror to think is thatyou’re singling her out to pick on her. If she survives this challenge and stays in the box, let her believe it was the judge who didn’t like her taste in casual wear, not you. We don’t want her taking it out on your case.”

Catherine offered to go up and give Phil a hand with his application so I could get on with what I had to do.

Laura buzzed me on the intercom. “Mo just called while you were dealing with Phil. Count her in. She’s already feeling achy and dizzy, just from talking to Mercer.”

I picked up a legal pad, checked my watch, and told Laura that I was on my way to the grand jury rooms on the ninth floor to officially begin the investigation into Gemma Dogen’s death. New York County seated eight grand juries a day to hear the scores of cases that required their decisions every month. Four of them convened at 10A.M. No felony could proceed to trial in New York State without the action of the grand jury.

But before I even had to worry about how and when we would be able to identify a suspect to indict for the crime, I had a more pressing need to be before the twenty-three people who constituted the grand jury. It is only through their power that a prosecutor has the legal authority to issue subpoenas to request evidence in a criminal investigation. Although more than half of the states in this country have abolished the system in recent years, it remains very much in place in the State of New York. No D.A. here has the power to demand the production of documents or the presence of witnesses in his or her office. Police reports and pathologist’s findings would be forwarded to me with a couple of phone calls. But medical records, telephone logs, security guard sign-in sheets, and the other paper links to potential evidence in a case like Dogen’s all had to be obtained with the permission of the grand jury.

Most citizens have no reason to know the purpose or function of this body, called “grand” to distinguish it from the “petit” jury of twelve that sits on criminal cases. Derived from British common-law practice, it was created to serve as a rein on prosecutors whose investigations were politically motivated or unjustified. And its rules are entirely different from those of the trial jury. It is a secret proceeding, to which no members of the public can gain admission; the defendant is entitled to testify, although he rarely does; the defense has no right to call witnesses; and those that the prosecution calls are not cross-examined. The duty of the grand jurors, after listening to the state’s evidence, is to vote a true bill of indictment when enough evidence exists to warrant a trial.

The waiting room was full of assistant district attorneys and their witnesses. The former were mostly bright-eyed and eager, busily picking up their caseloads of human misery on the first step toward a preparation for trial. It is what young lawyers came to offices like Battaglia’s to do, and they were generally happiest when juggling a lot of balls in the air at any one time. I watched them write out their charges in triplicate on forms that would be submitted by the warden to the member of each jury who had been designated to serve as the foreman. They stood shoulder to shoulder at an oversized counter in the front of the room as they worked against each other and the clock, to seek indictments on their cases.

Witnesses were a more somber accumulation-people who had been mugged or stabbed, relieved of their wallets or their cars, conned by strangers or kin, and who were anxious about both their victimization and their anticipated hours of frustration dealing with the court system.

Only two of my dozen colleagues scowled openly when I walked past them to the warden, who controlled the sequence of cases that were presented during the session. My presence in the waiting room, and my new assignment to a high-profile case, meant that I had come up to ask to be taken out of order and jumped over the line of grand larcenies and drug busts whose crews had been assembled for more than an hour.

“Relax, Gene. I’ll only be a minute. No witnesses. I’ve just got to open the investigation so we can start serving some subpoenas. I won’t hold you up.”

“Debbie’s got a five-year-old in her office down the hall. Father’s girlfriend scalded her with boiling water when she wouldn’t stop crying. She’s really a mess-”

“That goes first, obviously. I’ll just slip in after she’s finished.”

When the warden gave the signal that the jurors had a quorum, I phoned Debbie’s extension and suggested she bring the child down to testify. The badly scarred kid, her hair missing and her skull scorched on the left side of her head, clutched the hand of the prosecutor as she walked the gauntlet of lawyers, cops, and civilians. They paused together at the heavy wooden doorway of the jury room as Debbie looked the child in the eye to reassure her and ask if she were ready.

An affirmative nod was the reply and the door opened for Debbie to lead her by hand to the witness chair in the front of the room. The court stenographer brought up the rear. I had done it hundreds of times over the last decade-with women, men, adolescents, and children. I had seen the mouths of the twenty-three jurors drop open in gapes of horror, repelled by the damage one human being had inflicted on another. I recognized the traditional importance of the body and respected its power. But in addition, I understood how a manipulative district attorney could use the inherent imbalance of the process to his or her own end, so I also credited the more modern maxim that most prosecutors could indict a ham sandwich if they chose to do so.

The child was out after six minutes, having told her tale. Her father testified next, followed by the two police officers who had responded to the scene and made the arrest. A clean presentation-bare-bones, as we teach it-just the essential elements of the criminal act laid out by the assistant district attorney for the jurors. No need to try the case to them, as there is neither judge nor defe

nse attorney nor defendant himself in attendance.

Debbie and the steno rejoined us in the waiting room so that the jurors could begin the process of deliberating and voting. The buzzer, which signaled their decision, rang within seconds. No one who saw the child doubted that a true bill had been returned-the defendant was indicted for attempted murder.

The warden waved me into the room. I walked to the front and placed my pad and Penal Law on the table provided.

“Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. My name is Alexandra Cooper. I’m an assistant district attorney and I’m here to open an investigation into the death of Gemma Dogen.”

So far, no bells went off. I was facing the jurors, who were arrayed in amphitheatrical fashion opposite my position. Two rows of ten sat in a double-tiered semicircle, capped by three seats at the top from which the foreman, his assistant, and the secretary ran the proceedings. As usual, they were still holding newspapers in their laps and chewing on the bagels and muffins they had smuggled in past the posted signs that cautioned that no food was allowed.

“I am not going to present any evidence to you today, but I will be back throughout your term on the same matter. I’d like to give you a code name by which I will refer to the case whenever I appear before you. I think that will help you remember it since you’ll be hearing so many different presentations. The code will be ‘ Mid-Manhattan Hospital.’ ”

Not as clever as some of our reminders but it had the virtue of clarity. Jurors began to sit up and look more attentive. Several whispered to their neighbors, obviously explaining that this must be the stabbing of that woman doctor they had heard about on the news and read in their papers. Brown bags with breakfast remains were crumpled and stowed under seats. Two men in the front row leaned forward and gave me a careful once-over, as though it might make a difference when I finally returned later in the month to offer them up a murderer.

“I would like to add a special reminder today. As some of you may be aware, there are accounts of Dr. Dogen’s death in the newspapers and on television. When you come upon those stories, I must direct younot to read or listen to them.”

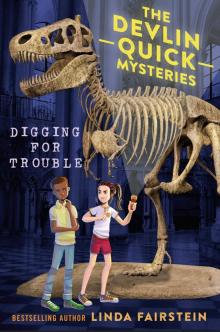

Digging For Trouble

Digging For Trouble Blood Oath

Blood Oath Likely To Die

Likely To Die Bad blood

Bad blood Cold Hit

Cold Hit Entombed

Entombed Final Jeopardy

Final Jeopardy Lethal Legacy

Lethal Legacy Killer Look

Killer Look Secrets from the Deep

Secrets from the Deep The DeadHouse

The DeadHouse Alex Cooper 01 - Final Jeopardy

Alex Cooper 01 - Final Jeopardy Deadfall

Deadfall Hell Gate

Hell Gate Terminal City

Terminal City The Bone Vault

The Bone Vault Silent Mercy

Silent Mercy Night Watch

Night Watch Death Dance

Death Dance Terminal City (Alex Cooper)

Terminal City (Alex Cooper) The Kills

The Kills Devil's Bridge

Devil's Bridge Into the Lion's Den

Into the Lion's Den