- Home

- Linda Fairstein

Death Dance Page 6

Death Dance Read online

Page 6

6

The janitor led us down to the third floor, through the electrical shop and the multistory paint bridges where crews of workers were constructing scenery, back to the interior point within the building where the air shaft bottomed out.

Only Mike, Mercer, and I entered the narrow passageway. The air circulation system had been turned off at Mike's direction and he led us in to check for any signs of life while we waited for someone from the medical examiner's office to make the decision about how to move Talya.

Mike kneeled at the wire-mesh cage, shining a torch-size flashlight into the hole, trying to get as close to her body as he could.

I flinched when the beam found Talya's head. Not much of it was intact. It didn't matter how many corpses I'd seen. The moment never got easier.

Mike was talking to Mercer, framing a description like the ones he'd heard week after week as he stood witness at the autopsy table in the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. "Probably a circular fracture of the cranial vault. Can you see that split through the hairline?"

The long, fine strands of Talya's hair were plastered against her scalp. She had gone into the shaft headfirst, it appeared, her neck twisted under the weight of her slim body.

The skull was actually split in pieces, looking like the blood-stained map of an intersection of five major highways.

Mercer differentiated the injury from a depressed skull fracture, the kind that occurs when an object crushes a small area of the head. "Must have been alive when she was thrown over."

The circular fractures radiated out from the point of impact, aggravated by the velocity of the dancer's descent and the height of the drop.

Blood was everywhere, pooled beneath Talya's ear and splattered all over the satin torso of her costume.

"You see her arms?" Mercer asked.

"Looks like they're behind her. Probably tied."

The legs that had been so distinctly Galinova's-long and lean, well muscled and with extension that had been remarked upon by every reviewer since her debut in Moscow more than twenty years earlier-were visible from beneath the ripped tulle skirt. The left one was twisted inward, the knee apparently knocked out of its joint as it bounced off the wall of the shaft. The right one, closer to us, seemed broken in half at the calf, the bone protruding through the Lycra tights that covered Talya's leg. There was no toe shoe on that foot, as there appeared to be on the other.

Mike moved the light like a wand, up and down the lines of the body, looking for any other marks or signs of injuries unrelated to the fall.

Behind me I could hear the voices of new arrivals. "Chapman? We're comin' in."

"Move it, Coop. That's Emergency Services."

I backed out of the space and greeted the crew from ESU. They were lugging just about every kind of device that could be imagined to cut through the metal grating.

While I listened to them work their way into the small cell-the caged area above the giant fan-that held Talya Galinova, one of the death-scene investigators appeared to do a cursory study of the body, declare the matter a homicide, and supervise the delicate removal of the remains to the basement of the morgue.

Mike and Mercer joined me to make way for Hal Sherman, who had to photograph the body from every aspect before anyone could move the dancer from her painful pose.

When that was done, Dr. Kestenbaum, the medical examiner on duty, put on his lab suit, gloves, and booties, looking more like a space traveler than a forensic pathologist as he approached the air shaft. Within minutes, Kestenbaum returned and signaled the ambulance crew to bag the body.

We circled around him to see what he had to say. "I think you could have done this without me."

"Yeah, doc," Mike said. "But what killed her?"

"Skull fracture. Broken neck with cervical spinal injuries. Hands bound behind her back so nothing to cushion the blow before the head struck. Massive contrecoup contusions-a classic result of a fall. You and I had one like that before, Mike."

I had seen the photos of the brain in Mike's case in which a man was pushed off the roof of one of the city's great museums. The brain rebounds backward from the skull after striking with such great force, leaving the devastating marks at the location directly opposite the point of impact.

The young doctor turned to me. "Doesn't look like your Baliwick, Ms. Cooper. The leotard and tights are in place. No signs of an attempt at sexual assault."

Mercer wasn't giving up the connection that would keep a Special Victims Squad detective in the case. "The murder may have been the result of a relationship she was involved in. Too early to tell. Alex and I are in this for the long haul."

I couldn't tell whether Mercer said this because he was professionally interested in who killed Talya or because he wanted to remain in the case for the purpose of shoring Mike up as we got him back in the saddle for what would now be a high-profile investigation.

"You'll want these things," Kestenbaum said to Mike, handing him several brown paper bags.

Mike opened the first one and passed it to me. Inside was one of Talya's pointe shoes-soft white satin with the hard surface at the front that allowed her to dance on her toes. The two ribbons that crisscrossed and laced around the ankles seemed to be missing.

"Did this tear off during the fall?" I asked.

"No," Kestenbaum said. "Check one of the other bags. The perp must have made her take one slipper off before he killed her."

Each piece of evidence was bagged separately, to prevent the transfer of any substance-even microscopic amounts-from one item to another. It was collected in ordinary brown paper, so that surfaces damp from blood or water would dry out, rather than mildew in the plastic. In a second bag, then, were two strands of ribbon.

"The shoe landed underneath her body. We'll have to study the pattern of the blood to see exactly how it spattered or dripped. Those ribbons were used to tie her hands behind her back. Much easier to toss her into the pit without her able to struggle or resist. I'm actually surprised there's no gag."

"That's 'cause this monster's turned off now. Sounded like a fleet of 747s on takeoff when we got here," Mike said. "Would have drowned out anything."

Mercer's gloved hand reached for the smaller bag. He removed the two pieces of ribbon, an ivory white satin that matched the color of the pointe shoes exactly, and examined them. The ends that had been sewn onto the shoe had been ripped off. He sniffed at the ribbons.

"Smells like mint, don't they?" he said, extending his hand to me.

"Yeah. Could be flavored dental floss. The girls are each responsible for their own shoes-breaking them in, coating the toes with resin, sewing on the ribbons," I said. The class that I took on Saturdays had several of American Ballet Theater's soloists in it. They often relaxed between sessions, stretched against the wall below the barres and covered in their leg warmers, preparing some of the dozens of shoes they danced through every season for the week's performances.

"Floss?" Kestenbaum asked. "We'll have the lab test to make sure."

"That's the latest thing in the studio-it's replaced old-fashioned thread 'cause it's stronger and thicker."

A small manila envelope was the third package Kestenbaum handed Mike. "Looks like your victim pulled a tuft of these oat of somebody's head."

There were eight or ten strands of hair, white and silky. "Were they in her hand?" I asked.

"Not when she landed. Hard to say, after being bounced against the walls on her way down. A few were clinging to the tulle skirt in the back, so they may have been in her fist before she got banged around."

"Will you be able to do mitochondrial DNA?" It was a much slower process used for human hair-and a different one-than that used with body fluids, and still more controversial in regard to acceptance in the courtroom,

"If she didn't get these out by the root, then, yes, we'll have to do mito. We'll send them down to the FBI overnight." This form of testing could be done when the entire root of the hair was not available for tra

ditional nuclear DNA work, using just the shaft that often rubbed or sloughed off against clothing or other surfaces.

"Where'd this come from?" Mike asked, removing a small black object from the last envelope.

"Not to worry. Hal got a picture before I moved it. It was likely to fall out when they picked up the body," the pathologist said. "It was caught in the netting of the skirt. Most likely an artifact of some sort that she picked up during the drop to her death. I didn't want to leave it behind because some defense attorney will end up seeing it in the photos and accuse me of throwing it away. I don't know what it is."

"You've been spending too much time under the microscope. You need to give your brain a rest and work with your hands every now and then," Mike said. "Never saw a bent twenty in your life?"

I leaned over for a look. It was a nail, bent at a ninety-degree angle in the middle.

"They're everywhere here. Go back to the design shop, they're probably what hinges every piece of scenery you see. When workers put the different panels of plywood together, after they've moved them onto the stage, they hammer 'em in place using these little suckers to hold them. I bet there's more bent twenties in the Met than there are peanut shells at Yankee Stadium."

"You getting ideas?" Mercer asked.

"Tell the commissioner this one will take a task force the size of an army. By the time we interview everyone on staff, run raps on all of them, check alibis, and begin to think about strangers who might have worked their way inside, I'll be old enough to put in my papers for retirement."

We started back toward the elevators. "Don't you think we ought to get this theater shut down for the night?"

"That's the first subject that reared its ugly head before you and Mercer got here this afternoon. I was turned down flat. Not even the PC can get it done, but he's got the mayor working on it. Why should a frigging murder get in the way of a few hundred thousand bucks at the box office?"

When the elevator doors opened on one, Chet Dobbis was waiting for us. "Word's spread around here pretty quickly. Rinaldo Vicci has gone to call Talya's husband, and I'll have to deal with the media. May I-may I see her before…?"

"Nope. You can pay your respects at the funeral home. This stuff isn't for amateurs," Mike said. "Better make some space for us. We'll be living under your roof for a while."

"I thought you'd do this from the station house, detective," Dobbis said, pulling tighter on the knot of the sweater wrapped around his neck. His narrow, elongated face looked pinched, as though he'd tasted something sour. "It's going to be rather disruptive to the other artists, to the people who work here. To our patrons, of course."

"Funny thing about murder, Mr. Dobbis. It often is. Put some of your divas on tranquilizers, but I expect this to be our headquarters till we find the phantom."

"And what do I tell Joe Berk, Mr. Chapman?"

"What do you mean?"

"He called here half an hour ago, looking for Talya. Do you want to break this to him or should I?"

7

The green velvet smoking robe with its coordinated paisley ascot over bare hairy legs was a striking choice of outfits for Joe Berk, who received the three of us at five thirty on a Saturday afternoon, but I was mostly fixated on his mane of fine white hair.

"You'll forgive me for not getting up, won't you? Which one of you is Chapman?"

Berk was reclining in a Barcalounger, unable to see me behind Mercer and Mike.

"I'm Chapman. This is Detective Wallace, and that's Alexandra Cooper, from the Manhattan DA's office."

"I didn't notice the young lady there. Sorry," Berk said, kicking down the footrest and getting to his feet. He approached us, exchanging greetings with the men, then bowed at the waist and reached for my hand, gesturing as though to kiss it.

He looked younger than I had expected, and more fit. Mike had used the word thick to describe Berk, but it was burliness rather than weight, and it gave him a powerful air that was consistent with the arrogance he exuded. *

"My secretary said you wanted to see me about a missing person. Who's that?" he said, picking up a cigarette holder, sticking a Gauloise in the tip and searching for his lighter. Berk moved behind his desk and offered us three chairs that were arrayed in front of it. "Who'd you lose?"

It was easier to get people to cooperate with investigators- especially if they could be linked to the crime in any way-by asking for help with someone who's gone missing rather than invoke the word murder.

"Natalya Galinova," Mike said.

"You're a little behind the breaking news, aren't you, boys?" Berk looked back and forth between Mercer and Mike. "Who're you kidding here? Joe Berk? Talya is dead. You think I'm an idiot?"

"Seems to me that half an hour ago you didn't have a clue where she-" Mike said before being interrupted by the buzz of an intercom.

Four of the buttons on Berk's large phone console showed flickering red lights and he pushed the one closest to him, holding a finger up in Mike's direction. "Yeah, babe? Tell that rat bastard when his check clears, then I'll take his call. And release all my house tickets for tonight. Anyone on your list. It looks like I'm going to be with these comedians for a while." He disconnected the call. "Gentlemen?"

"Who told you about Ms. Galinova?" Mike asked.

"Told me what?"

"That she's dead."

"It's some kind of secret?"

"It was until-"

"Yeah, I heard you. Half an hour ago. You know how many people call Joe Berk every thirty minutes?" he said, sweeping his hand over the blinking dials on the console.

"Nathan Lane comes down with a sore throat, my phone rings. Bernadette Peters gets indigestion, somebody rings me. The Lion King has diarrhea, I'm the first to know."

"Miss Galinova didn't work for you, did she?" Mike asked.

Berk dragged on the cigarette. "Footlights and fantasy, Mr. Chapman. That's what I'm about. Anybody who ever walked the boards wants to work for me."

The intercom buzzed again. Berk gave Mike a full palm now. "Yeah, babe?"

He listened while the secretary told him who was on the line. "Gotta take this call, guys."

Berk rested the cigarette holder in an ashtray and pressed his fingers against his temple. "Bottom line, that's all I wanna know. Yesterday you told me thirty-five. We going over that yet?" He waited for an answer. "You kidding me? It's grossed over three billion worldwide. Soup it up, Joey. Hands down, it's the most popular entertainment property ever. Don't screw with me-I got a lady here, Joey, or I'd tell you how I really feel."

"Can you hold these calls till we're done?" Mike asked.

"Hey, for thirty-five million, I'd suggest you hold your questions till I'm done, buddy," Berk said, turning his attention to me. "We're taking Phantom of the Opera to Vegas. Custom-made theater at the Venetian, a flying chandelier bigger than a boat, and very few people with Joe Berk-size pockets who can make it happen. Broadway goes Vegas. Get a hundred bucks a seat without even blinking."

"We were talking about Ms. Galinova," Mike said. "Look, Mr. Berk, we understand you were at the Met last night."

"Absolutely."

"But missed the show."

"Not my thing, ballet. The music puts me to sleep, the broads are too skinny for my taste, the boys run around with pairs of socks wadded in their crotches to make themselves look like they're well hung. Give me Shakespeare or give me schmaltz and I can pack you a full house. Not the ballet."

"But you were going there specifically to see Ms. Galinova, weren't you?" Mike asked.

"Talya invited me to the gala. Look, I tried very hard to make it. She's a classy dame, but I got a schedule of my own. We had an understudy going on in one of our shows last night and I had to see the first act for myself to figure out whether she's got the stuff to take over the lead. I was late for Talya's scene. So sue me."

"What happened when you arrived at the Met?"

"Nothing happened. Meaning what?"

"Meaning what did you do wh

en you found out they wouldn't seat you?"

"I thanked my lucky stars for my brilliant timing and went back to the dressing room to wait for her."

"The ushers just let you inside? No problem?"

"Why? Some jerk didn't know me, I had to spend a few minutes educating him? Next time he will."

"You knew where the dressing room was?"

"Yeah, sure I did. I've been there before."

"Recently?"

"Yeah, yeah, yeah. Talya wanted to talk to me, I went. She tad time off during the rehearsals, I went."

"To talk about ballet?"

"Don't be funny, detective. I told you that doesn't interest me. Talya needed Joe Berk, Mr. Chapman, not the other way around," he said, poking his forefinger into his broad chest. "She wants to be-wanted to be-in a production of mine. She wanted me to make her a Broadway baby."

"Any show in particular?"

"That would make a difference to you? You want to put up ten percent, be a backer?"

Mike was as annoyed as if Berk were scratching a fingernail along a blackboard. "The only difference it would make is whether I believe you."

"Like I have to worry if you do or you don't." Berk laughed. "You know the story of the girl on the red velvet swing? Evelyn Nesbit."

I recognized the Nesbit name and knew she'd been involved in some kind of scandal, but couldn't bring it to mind. Mike answered. "Harry Thaw. Stanford White. The old Madison Square Garden. Sex, infidelity, money, murder-the story's got it all."

"Bravo, detective. Opening-night seats for you, sir, on the aisle. Murder, Miss Cooper. A good old-fashioned Manhattan murder. Your detective friend clearly knows his true-crime stories. He'll tell you later. Otherwise you'll have to buy tickets. You," Berk said, winking at me, "I might invite you myself. Leave the coppers home."

Mike had majored in history at Fordham College. There was nothing he didn't know about military history-foreign and American-and his congenital fascination with the world of policing made him an expert on New York's darkest deeds.

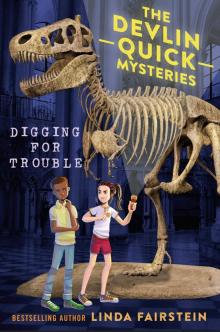

Digging For Trouble

Digging For Trouble Blood Oath

Blood Oath Likely To Die

Likely To Die Bad blood

Bad blood Cold Hit

Cold Hit Entombed

Entombed Final Jeopardy

Final Jeopardy Lethal Legacy

Lethal Legacy Killer Look

Killer Look Secrets from the Deep

Secrets from the Deep The DeadHouse

The DeadHouse Alex Cooper 01 - Final Jeopardy

Alex Cooper 01 - Final Jeopardy Deadfall

Deadfall Hell Gate

Hell Gate Terminal City

Terminal City The Bone Vault

The Bone Vault Silent Mercy

Silent Mercy Night Watch

Night Watch Death Dance

Death Dance Terminal City (Alex Cooper)

Terminal City (Alex Cooper) The Kills

The Kills Devil's Bridge

Devil's Bridge Into the Lion's Den

Into the Lion's Den