- Home

- Linda Fairstein

Blood Oath Page 3

Blood Oath Read online

Page 3

Her shoulders hunched up—her expression still blank—as though a shrug answered everything.

“Can you go back, Lucy?” I knew that was a different question than would she.

“Yeah. My aunt Hannah has room for me. Hannah Dart. She lives in Winnetka—one of those fancy Chicago suburbs. It’s my cousins who don’t have much use for me.”

“It would help if you give me all her contact information,” I said. “We can use your aunt’s name in court as long as I can call her first to get her to agree.”

I moved my chair a few inches closer to Lucy, our knees almost touching.

“Would you tell us about the murders you witnessed?” I asked. “Mike’s better at handling homicides than any ten detectives I’ve ever met.”

“The murders aren’t the problem,” Lucy said. “They were solved. That bastard’s still in jail.”

“The cops took Lucy from the precinct,” Mike said, “up to the Homicide Squad because when they ran her name check in the system, it came up on the old Homicide investigation—the one she was a witness in.”

“But those murders must have something to do with whatever your issues are, Lucy,” I said. “Won’t you please take us that far?”

“Lucy wouldn’t give the lieutenant the time of day,” Mike said. “He told me that she saw some old photograph hanging on the wall in the station house and kind of freaked out.”

“That’s not a crime, is it?” she said, slumping down and crossing her arms. “Freaking out?”

“A photograph of what?” I asked. “A mug shot? The perp who committed the murders?”

Lucy almost managed a laugh. “Not a mug shot, Ms. Cooper. Not even close.”

I needed to find a way in, to penetrate her icy veneer. “Will you talk to me about the man who hurt you? Tell me what he did?”

“There’s no point in that, ma’am. No one ever believed me when I spoke up.”

“Try one more time, please,” I said. “It’s my job to believe people who’ve been hurt.”

“Then how come you’ve been away from your job for three months?” she asked. “Did you stop believing?”

“Sorry, Coop,” Mike said. “I’m the one who told Lucy that you’re just back to work.”

I didn’t take my eyes off her face as I steadied myself to speak to her. I didn’t often reveal my personal story to witnesses in my office. “Because I got hurt, too. I know what it is to be scared to death, to have someone treat me so badly I didn’t know how I’d ever recover from it.”

Lucy met my stare head-on. “I bet you got believed, didn’t you?”

She nailed me on that one.

“Yes. Yes, I did,” I said. “And that helped me a lot.”

She smirked at me, and I ignored it.

“Why don’t you tell me what you witnessed all those years ago?” I said. “Can’t we start with that?”

“I’m sick of telling that story.”

“Well, Mike and I have never heard it.”

She kicked her left foot back and forth, as regularly as a pendulum, while she considered answering me.

“Did the case involve anyone in your family?”

“No, ma’am. Nothing like that.”

“Was it here, in Brooklyn?” I asked, thinking about the photograph on the wall in the station house that had spooked her.

She shook her head.

“Chicago, then?”

“Nope. First time I ran away from my aunt’s house,” Lucy said. “Iowa City.”

“Whoa. That’s hours from Chicago,” I said. “And you were only fourteen years old. How did you get there?”

“I took a bus. Three hours is all.”

“Alone? Did you run away alone?”

“No way. I was with my friend Austin.”

“Your boyfriend?” I asked.

“That’s not what I said, was it?” Lucy asked. “He was just a good friend, from my old ’hood. He was sixteen, so I trusted what he told me. We took the bus to go meet up with his cousin Buster, who lived in Iowa City.”

“How did that go?”

“It was fine at first. Buster’s mother was happy to see Austin, and she liked me because I helped with the dishes and the laundry.”

“I’m glad she liked you,” I said. “But your aunt must have been upset.”

“She upsets easy. Always will,” Lucy said. “Everything was okay—Buster’s mother kept my aunt in touch and all that. It was summertime, so she couldn’t fuss about me missing school, and the three of us used to hang out in the park. Hickory Hill Park. We didn’t do anything wild. Just listened to music and met up with friends of Buster’s.”

“So it’s not either one of them—Austin or Buster—who hurt you?”

Lucy shook her head from side to side. “They were my friends.”

Her luminous hazel eyes looked as though they were filling with tears.

“What happened, Lucy? Can you tell us that?”

She bit her lip, showing emotion for the first time since we had started talking.

“They’re both dead because of me,” she said.

I reached out to put a hand on the knee of her jeans.

“That can’t be the reason.”

“It is,” Lucy said, jerking her leg to the side and raising her voice. “It’s because of me they were murdered.”

“What did you do, Lucy?”

“I look white, Ms. Cooper. That’s what I did,” she said. “There was this madman—really a madman—who was going around the country with his AK-47. He was shooting at people, killing people he didn’t even know.”

“Austin and Buster?” I asked. “This guy shot them?”

Lucy nodded as tears rolled slowly from her eyes to the tip of her chin.

“He shot them because what he saw was two black guys hanging out with a white girl,” Lucy said, talking so fast now she had to pause to catch her breath. “In Hickory Hill Park, on a ball field, at six o’clock at night, without so much as saying a word to us.”

“A sniper, right?”

“Yes,” Lucy murmured.

“Killing black men in a public park,” I said.

“I told you that.”

A madman going around the country, she had also said. “And the same guy killed a man in Salt Lake City for the same reason, didn’t he? For jogging with a white woman.”

She nodded.

“In Liberty Park, right?”

“Yeah,” Lucy said.

“And an interracial couple playing tennis in Grant Park in Portland, Oregon,” I said, pulling from memory the facts of a landmark federal case, tried by two prosecutors using a novel legal theory.

“You know Lucy’s case?” Mike asked.

I held out my left arm in his direction to silence him. I had her talking now and I didn’t want her to stop.

But Mike’s comment triggered Lucy to realize I remembered her trial. “You know about it?”

“I know of it,” I said, trying to keep her calm. “From casebooks and newspapers. The same guy even tried to kill a man in a park in Manhattan. Fort Tryon, up near the Cloisters museum.”

Mike nodded.

“Every prosecutor in the country learned about it,” I said. “It’s historic.”

Lucy wiped the tears off her right cheek with her fingers and stretched back her head so that she could look up at the ceiling, avoiding eye contact with me.

“The sniper was a murderous white supremacist, Lucy,” I said. “It’s not because of you that Austin and Buster were killed.”

“I was sitting on the bench, so close to Austin that pieces of metal shattered and flew into my neck—from the bullets,” she said, rubbing the left side of her neck.

Shrapnel, I thought to myself. I remembered that from the media coverage, too. The

teenage girl who was almost another casualty of the bigoted killer.

“So he’s the man who hurt you,” I said, jamming the pieces of the puzzle together faster than I should have done.

“I told you no. I already said it wasn’t him.”

“Sorry. I just assumed—”

“I don’t even remember the pain from the shooting,” she said. “Nothing can bring back Austin and Buster, but at least that racist asshole will never see the light of day again.”

I was sitting bolt upright now, focused on Lucy but trying to figure out what we could do for her as the past seemed to be conflating with her present state of rootlessness.

“Look, Lucy,” I said, “we can’t make any of that go away, but we can certainly try to improve your situation. Dismiss your warrant, find you housing, get you counseling. We can do all of that.”

“I want him to leave the room,” Lucy said, pointing at Mike as her manner changed completely.

Her entire mood had shifted and her anger seemed suddenly palpable.

Mike laughed and ran his fingers through his thick hair. “An hour ago I was your best friend, kid. Now you’re booting me out of here?”

Lucy was stone-faced.

“Why don’t you check with Laura?” I asked him. “See if there are any messages I need to know about. And go to Helen Wyler’s office and get her cell phone out of her top desk drawer. Call TARU and tell them I need an overnight download of every text she’s had from her complaining witness in the last three weeks.”

“Two to zip in favor of my exit, and you’re giving me grunt work to do as well,” Mike said, pushing back from my desk and walking to the door. “See you later.”

I waited until the door closed tightly behind him.

“Is this better for you, Lucy?” I asked.

“Maybe,” she said. “I don’t know yet.”

“Is there something you want to tell me?” I said. “Just me?”

“What are you going to do with the information, if I give it to you?”

“I can’t give you an honest answer yet. That’s just because I don’t have a clue what you have to say.”

“I told people before,” Lucy said. “I told them five years ago, the first time I came to New York, but nobody did anything about it. Now it’s probably too late.”

“Try me, Lucy,” I said. “The lieutenant who met you in Brooklyn earlier today obviously thought it was something I might be able to help you with. Why not try me?”

She looked toward the closed door, and I was afraid she was going to get up and walk out.

“I’m sick of reading these stories in the papers every day, all these women talking about shit that happened to them twenty years ago,” Lucy said. “Nobody even doubts them the way people turned their backs on me.”

This conversation was picking up intensity as Lucy got to the reveal. It wasn’t about the post-traumatic stress of witnessing the murders of her friends or about cleaning up the warrant that had been held over her head for five years. Somewhere in this nightmare of a life story, there was a sexual assault that hadn’t been credited when Lucy tried to report it.

“Well, it’s my turn now,” she said, stabbing the center of her chest with her forefinger, over and over again. “Me, too, Ms. Cooper. Me, too.”

THREE

“How far did you get with Lucy after I left the room?” Mike asked.

“She shut me down pretty quick,” I said. “I think she’s testing me, to see if I’m really going to do the right thing.”

“How so?”

“She said she was hungry and tired and felt dirty and had nothing more to say to me until I kept my word.”

“Your word? Lucy’s challenging that?” Mike said.

“She wants her old case dismissed, and I said I could do that.”

“Where is she now?”

“Maxine is glued to her,” I said.

My paralegal had worked with me for three years since graduating from college. She was as good as any prosecutor at evaluating cases and she had a heart of gold that made her a favorite of the survivors who passed through our offices.

“I set them up in the conference room with strict orders to Max not to let Lucy out of her sight. Laura ordered in sandwiches and drinks, then walked over to Broadway to buy some clean underwear and a couple of outfits at the Odd Lots discount store.”

“What’s next for Lucy?”

“A hot shower in the executive ladies’ room, a change of clothes, and a nap.”

“Then you’ll have another go at her,” Mike said.

“Over and over, till I get the story,” I said. “How’d you do with Helen’s phone?”

“The tech guys are on it. No big deal. They’ll pull up those texts later today and have the phone back to her before midnight.”

“Good. I’ll let Helen know,” I said. “Meanwhile, get on the phone to Brooklyn South Homicide and have someone take close-ups of all the photographs on the wall that Lucy might have seen. Email them to me and let’s see if she can pinpoint the one that set her off.”

“You think—?”

“I think maybe the reason she turned on you is that once she decided to tell me about the man who assaulted her—instead of telling any of the detectives at the squad—chances are it’s because she saw a photo of someone she recognized. Maybe one of the cops on the case,” I said. “It’s not very hard to connect those dots. Likely the guy she freaked out about had a badge and you’ve got a badge. Could be as simple as that.”

“A cop?” Mike said, glaring at me with his fists balled up against his waist. “Where are you going with this now, Coop? You’re saying some cop raped a fourteen-year-old kid, just because she’s going all weepy on you? You do believe that’s why she wanted me out of your office, don’t you?”

“Something set her off in the station house, didn’t it? An old photograph, probably cops from that command.”

“Yeah,” Mike said. “I’ll tell you why she got set off. The reality that a warrant was dropping that would keep her in the slammer for a few days. Have you checked her story with the aunt yet? And what do you really know about that case she testified in? Why would the NYPD have been involved?”

“The killer’s name in Lucy’s case is Weldon Baynes. Welly, he called himself, if you want to see what I ‘really’ know about it,” I said, crossing my arms and sitting on the edge of the desk. “He was from Athens, Georgia, before he set out on his odyssey to kill black men, including her companions, Austin and Buster.”

“Where did his overload of hate come from?” Mike asked.

“You’ve known enough bigots. Baynes was probably taught to hate his entire life, I’d guess. I don’t know what the psychobabble was about his history, or I just don’t remember that. All that’s certain, I think, is that he wanted to start a race war—ignite some local fires and hope they’d spread across the country.”

“But always targeting black men with white women?”

“Always. The couple in Fort Tryon Park had just left the Cloisters museum. They were both graduate students in art history at Columbia, not lovers,” I said. “You know how deserted it can be up there on the Heights.”

Mike and I had handled a murder case that involved the Cloisters early in our professional partnership. The museum housed a spectacular collection of medieval art that had been gifted to the city, along with the parkland of Fort Tryon, by John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

“That pair just got lucky?” Mike said. “I wasn’t working Homicide then. Maybe that’s why I’m not calling it up.”

“Those two got very lucky, and that’s an understatement. The sniper took several shots but missed the young man completely and got away clean. He was only linked to the other murders by the bullets, which the FBI compared because of the location—a public park, again—of the attempted murder.”

“So NYPD cops were assigned.”

“From our Hate Crime Task Force, with some experienced Homicide cops thrown in by each of the cities, including us, who partnered with FBI agents. Call Lieutenant Peterson—he’ll tell you who was on the national team from our force,” I said. “Get some names and we’ll try to match them to the photos from the Brooklyn squad room.”

“You think I’m snitching on some detective who’s probably retired to the Outer Banks by now, enjoying his pension and sucking on his second margarita this very minute, when we don’t even know what this kid’s story is? When she’s calling the shots and you’re eager enough to fall for that,” Mike said, running his fingers through his dark hair, rather than pounding his fists on my desk. “Get yourself another rat, Ms. Cooper. Get yourself some misfits from Internal Affairs.”

I walked to my chair and picked up the phone. “I’ll run down Lucy’s story,” I said. “I promise you that. Right now, though, she has the benefit of the doubt.”

“Of course we give her the benefit of the doubt, once she opens up and tells her story,” Mike said, headed for the door. “But you know I’m not going to start attacking men—cops, no less—who haven’t been accused of anything.”

“It’s my job to get that story, and I have to use whatever tools are available to do so,” I said. “Lucy reacted to something she saw in a photograph? Then I need to see that photo, too.”

Mike’s hand was on the knob, his back turned to me.

“And you, Detective Chapman, are a mandated reporter of child abuse under the Family Court Act of the State of New York,” I said. “Walk out my door and you’ll be in very hot water.”

“The only two temperatures you know, Coop. Very hot and boiling,” Mike said, facing me again. “That’s why you’ll never be district attorney. You’ve got no thermostatic control for your attitude adjustment.”

“I’ll never be DA. because it’s a job I don’t want. Going around to all those party clubhouses and making deals or promises that an honest prosecutor shouldn’t make. Rubber chicken dinners and christenings and bar mitzvahs for the kids of high-rolling donors every weekend? I couldn’t stand a life like that,” I said. “That’s why I’ll never be DA.”

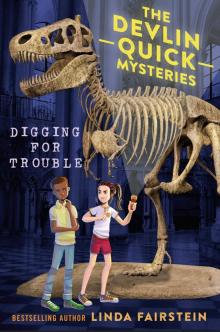

Digging For Trouble

Digging For Trouble Blood Oath

Blood Oath Likely To Die

Likely To Die Bad blood

Bad blood Cold Hit

Cold Hit Entombed

Entombed Final Jeopardy

Final Jeopardy Lethal Legacy

Lethal Legacy Killer Look

Killer Look Secrets from the Deep

Secrets from the Deep The DeadHouse

The DeadHouse Alex Cooper 01 - Final Jeopardy

Alex Cooper 01 - Final Jeopardy Deadfall

Deadfall Hell Gate

Hell Gate Terminal City

Terminal City The Bone Vault

The Bone Vault Silent Mercy

Silent Mercy Night Watch

Night Watch Death Dance

Death Dance Terminal City (Alex Cooper)

Terminal City (Alex Cooper) The Kills

The Kills Devil's Bridge

Devil's Bridge Into the Lion's Den

Into the Lion's Den