- Home

- Linda Fairstein

Cold Hit Page 17

Cold Hit Read online

Page 17

“And his illness-he was still working until recently, even with his heart condition?”

Mrs. Varelli snapped at me. “Illness what?”

“I, uh, I knew that a doctor had come when he collapsed.”

“A touch of arthritis, that’s what the doctor was for. Marco’s skill depended on two things, his eye and his hand. Neither one of us-no pills, no machines, no medicines. He only had a doctor to help him when his hand ached from the arthritis and it hurt him to hold a scalpel for so long. Un po’ di vino, Marco believed in. The medicine from the grapes.”

“It was his heart that gave out,” I said, hoping it was gentle enough a reminder of what the doctor had told the M.E.’s pathologist.

“There was nothing wrong with Marco’s heart. His heart was so good, so very strong.” Mrs. Varelli became tearful.

“Were you always in the studio with your husband?”

“No, I was rarely there. We have an apartment in the same building. We had our coffee together in the morning, then he would go upstairs to work. Back home for lunch and a nap. Then more work, always. Sometimes into the evening, if he found himself in the middle of a surprise or a painting he had come to adore. Then he would come home to bathe himself, to get rid of the oil and varnish and streaks. Together we would go off for dinner, alone or with friends. A simple life, Miss Cooper, but a very rich one.”

“Had you ever met Denise Caxton?”

“It was her husband I met first. I can hardly remember when, it was so long ago. He was not a warm man, but he was very good to Marco. Lowell Caxton bought a portrait at an auction house in London, maybe thirty years ago. It had been miscatalogued in England and sold as an unidentified portrait of a young girl. Lowell bought it only because he said it reminded him of his wife, whichever one that happened to be at the time. He didn’t believe it had any value, and he brought it to Marco simply to clean it up to be hung.

“But Marco thought she was a beauty, too. ‘Overpainted,’ he complained to me every time he came downstairs. He didn’t use many words, Marco. He didn’t need to with me. Days and nights he worked on it, until there was life in the child’s face and her petite blue dress had texture and the warm glow of silk. One afternoon, Marco came down for lunch. I give him his soup and he looks across the table. ‘ Gainsborough,’ he said to me, ‘it’s a Gainsborough.’ Every museum in England wanted to buy it back.

“Many people would just have paid Marco the price he asked for the restoration, and still my husband would have been happy. Lowell Caxton did that. But then he came back the next week, when Marco had come home for his lunch. I let him in the house-that’s when I met him. He had under his arm a small package wrapped in brown paper. It was a Titian-very small, very beautiful. We have it still. You come to my home, you’ll see it.”

“In your apartment? A Titian?”

“But so very little. It’s a study, just a piece of one of his great works. You know The Rape of Europa?”

Of course I knew it. Everyone who had ever taken an art course in college had studied it. Rubens had called it the greatest painting in the world. And I had seen it many times because it was part of the collection at the Gardner Museum. Was this just another coincidence? “When did you say Mr. Caxton gave you the Titian?”

Mrs. Varelli thought for a moment. “Thirty, thirty-five years ago.”

Before Denise, before the Gardner Museum theft.

“And Denise Caxton, was she a client of Mr. Varelli’s?”

“First she came many times with her husband. Then alone. Then with other people-maybe dealers, maybe buyers. I never met them in the studio. Sometimes Marco would tell stories about them.”

“Did he feel the same way you did about Mrs. Caxton?”

Mrs. Varelli tossed back her head and laughed. “Of course not. She was young, she was quite beautiful, and she knew how to make an old man feel wonderful. She’d practice her Italian on Marco. She’d flatter him and tease him and bring him fascinating paintings to examine. Always looking for gold where there was none. Wasting Marco’s time, if you ask me.”

“Do you know who the men were that she brought recently?”

“No, no. For this, I give you the names of my husband’s workmen. Maybe they were introduced or can tell you what these men looked like. You give me your card, and next week I call you with their telephone numbers.”

“Is that the only reason you didn’t like Denise?”

“I don’t need many reasons. She was trouble. Even Marco thought she was trouble.”

“How, Mrs. Varelli? What did he tell you about her?”

“Like I said, Miss Cooper, Marco didn’t use a lot of words. But these past few months, on the days that Mrs. Caxton came to see him, he didn’t come home smiling like he used to. She was trying to get him to work on something that upset him, gave him agita. That he did say. ‘At this age, I don’t need any agita. ’”

“But didn’t he get any more specific than that?”

“Not with me. I was just glad he didn’t want to work with her any longer. He didn’t seem to like the people she was bringing around.”

“Did Mr. Varelli talk about Rembrandt ever?”

“How could one make his life in this world and not talk about Rembrandt?”

I was grateful that she had not responded by saying what a stupid question I had asked. “I mean recently, and in connection with Denise Caxton.”

“You don’t know, then, that Marco is”-her chest heaved visibly as she breathed deeply and changed the wording. “Marco was the world’s leading expert on Rembrandt, no? Perhaps you’re too young to know the story.”

Mrs. Varelli went on. “Rembrandt’s most famous group portrait is called The Night Watch. Have you ever seen it?”

“Yes, I have. It’s in Amsterdam, at the Rijksmuseum.”

“Exactly. Then maybe you know that originally, more than three hundred years ago, it had a different name.”

“No, I’ve only heard it called by this one.”

“When he painted it, it was entitled The Shooting Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq. Over the decades, it became so covered with grime that people assumed that the setting was at nighttime-the name you know it by. Well, after World War Two was ended-in about nineteen forty-seven- when Marco was just getting a reputation as a restorer, he was part of the team of experts put together to restore the enormous painting. During the cleaning, it lightened brilliantly. That’s the first time anyone in the twentieth century realized that it wasn’t a night scene at all.

“Marco was the only member of that restoration group still alive fifty years later. When anyone-and I mean anyone, Miss Cooper-has a question about the attribution of a Rembrandt today, it was only my Marco who knew the truth. Monarchs, presidents, millionaires-they all came to see Marco Varelli about their paintings.”

“Denise Caxton, did she ever bring him a Rembrandt?”

“This I don’t know.”

“Did your husband ever say that she or anyone else asked him to look at paint chips recently?”

Again Mrs. Varelli looked at me as though I had no brain at all.

“That’s what my husband did every day of his life. Paint, paint chips, paint streaks, paint fragments. From this, Miss Cooper, come masterpieces.”

“Excuse me, Alex. Could I see you a minute?” Mercer was speaking to me from the hallway.

“May I go back to Marco now?”

“If you’d give us another few minutes, Mrs. Varelli, we’ll be out of your way,” he said to her.

I thanked her for her graciousness at such a terrible time and walked back to the room in which the coffin rested. Mike was standing next to the dead man’s head.

“I hope by paying your respects to the deceased you got more than I did from the widow,” I said to them as I reentered the room. “A bit of art history and a hunch that Denise Caxton was nothing but trouble.”

“Then I’d say Mrs. Varelli’s got great instincts. Remember that case I had a few

years back in Spanish Harlem? The Argentinian dancer, Augusto Mango, who died prematurely during a sexual encounter with a rabid fan?”

“Very well.”

“You know how we found out it was murder and not a bad heart?”

“No.”

“Some doctor declared him dead at the scene. I think he must have been a podiatrist. Then, at the funeral parlor, while they were combing his hair into place, the mortician found a bullet hole in the back of his head. Small caliber, barely the trace of an entry. The fan’s husband was the killer. Post headline was Don’t Tango with Mango.

“Well, Mr. Zuppelo wouldn’t make such a good barber.”

Mike carefully turned Marco Varelli’s head away from us and smoothed the thick white hair back from his left ear, much as he had done at Spuyten Duyvil when we first saw the body of Denise Caxton. There was the unmistakable mark that a bullet had pierced the skull of the gentle old man.

17

“Criminal court press room-where every crime’s a story and every story’s a crime. Mickey Diamond here.” The veteran New York Post reporter had covered the courthouse for longer than anyone could remember, and answered the phone with his usual élan on Thursday morning.

“What did you think you were doing by running that story this morning?” I asked when I called, trying to control my temper.

Pat McKinney had left a copy of the page-three clipping on my desk, quoting me in an article about the Caxton murder investigation. Battaglia had an inviolable policy about assistants talking to the press. He enforced it rigidly, and he was right to do so. With more than six hundred lawyers in the office and three hundred thousand matters a year coming through our complaint room, it would have been insane to let prosecutors comment on cases they handled. First I had called Rose Malone, urging her to let Battaglia know that Mickey’s feature was pure fiction, and then I had dialed the newsroom.

“Slow news day, Alex. My editor was begging me for a story.”

I looked at the lead paragraph in the piece, in which Diamond attributed to me a statement about a major break in the case.

“If we’re close to a solution, as you say I say, then it truly is news to me,” I told him. The story reported that, working closely with detectives from the Manhattan North Homicide Squad, I had discovered the motive in the Caxton killing and an arrest was imminent. “Battaglia will be furious when he reads this. It’s bullshit, but now he’ll get pressure from the mayor to make an arrest, and we don’t even have a suspect yet.”

“The truth is so rare, Alex. I like to use it sparingly.” He laughed at his own joke, knowing that I wouldn’t. “Straighten me out. Give me some real scoop to go with. Maybe this’ll make the killer show his hand-he’ll think you know more about him than you do.”

“Thanks for the help, Mickey. When he turns himself in because of your story, I’ll make sure you get the reward money.” If nothing else, I confirmed that word of Marco Varelli’s murder had not yet leaked to the press. Diamond would have been all over me if he’d heard what we had discovered last night.

We had broken the news to Varelli’s widow just as mournershad gathered for the evening visit to the funeral home. Her initial shock at the fact that her husband had been nated was replaced with her proud resolve that she had known he had not died of natural causes. Bravely, she composed herself and greeted their friends and associates for more than two hours, while we mingled with the small crowd in the room.

She had finally thanked Chapman warmly and then turned to tell me good night. “You see, Miss Cooper, I was sure that Marco Varelli would never have chosen to leave me. Such was his love, such was his life.”

The funeral was to be on Friday, after the second night of the wake, and she invited us to come to her nearby apartment the next week.

Mike had gotten her permission to seal Marco’s atelier last night and secure it with patrolmen. He would go back later today to process it with the detectives from the Crime Scene Unit. We needed her, or one of Varelli’s workmen, to help discover whether any artworks or valuables were missing. That might have to wait until after the burial.

Finally, when everyone left the dingy funeral home, Mike and Mercer had arranged for the Medical Examiner’s Office to pick up the body of Marco Varelli for an autopsy.

I had come downtown to work, busying myself in the review of new cases till I could meet Mike or Mercer in Chelsea. We were going back to Galleria Caxton Due to talk to Bryan Daughtry again, as well as to oversee the execution of the search warrant.

It was Mercer who phoned at eleven thirty to tell me he was leaving his office to go to West Twenty-second Street. Mike had witnessed the proceeding on Varelli at the morgue, which had validated his discovery at the funeral parlor, and would join up with us in Chelsea.

I drove my Jeep up to the gallery thinking about Denise Caxton, Omar Sheffield, and Marco Varelli. What common factor in their lives so closely linked them in death?

I parked right in front and walked to the Empire Diner, where I sipped another cup of coffee until the guys arrived a few minutes later.

“You got the warrants?” Mike asked, slipping into the booth along with Mercer, who had met him at the front door.

“Everything we need.”

We walked across the street and down the block, where the entrance to the gallery’s garage was blocked by a radio car. One of the uniformed officers saw us coming, recognized Mike, and got out to say hello.

“Hey, Chapman, how’s it going? Been a long time. I thought you did steady midnights?”

“Used to be, Jack. Now I’m afraid of the dark-doing day tours. Any action here?”

“He ain’t givin’ us any trouble. A little pedestrian traffic around, but no packages going without gettin’ searched, and no trucks in or out. Same report from yesterday.”

A receptionist met us inside the front door. “Mr. Daughtry thought you might be coming in sometime this afternoon. He’s upstairs with a client. I can make you comfortable down here, if you’d-”

“No thanks,” Mike said, ignoring the young woman and leading us to the elevator in the far corner. When we reached the top floor and stepped out onto the landing, there was no sign of Daughtry on the walkway. Mercer headed over to see whether he was in his corner office, while Mike and I looked out at the old railroad tracks again.

“My father used to tell me the stories about the gangs from Hell’s Kitchen who terrorized the train lines-the Hudson Dusters, the Gophers. When he was a kid, he hung out in a saloon right up the street here, running errands for a guy named Mallet Murphy. Called him that ’cause he’d crack disorderly customers over the head with a meat hammer.”

Mike leaned back against the waist-high iron rail as he looked out at this view of Chelsea. He couldn’t have been any happier if you’d sat him at the top of the Eiffel Tower. This was his father’s home turf, and the neighborhood held his family roots.

“This view could change my whole opinion of both Denise Caxton and Bryan Daughtry. It’s really cool that they left the old tracks in place.” He turned and noted the Plexiglas doorway that led out of the gallery onto the tracks.

“Hey, Coop, someday after me and Daughtry have put our differences aside, I’ll walk you and Mercer out that very door, onto the tracks, and take you as far downtown as it goes. Tell you stories about real gangsters and show you where the bones are buried.”

“We’re down here, Mr. Chapman. As long as you’ve made yourselves at home, why don’t you come tell me what you need?” Daughtry called up to us from somewhere a level or two below. I couldn’t see him from where I was standing, but he had obviously been alerted to our arrival.

The catwalk around the edge of the upper floor was about four feet wide. The three of us walked around its perimeter until we came to a metal staircase that led down a level.

Here the space extended out over the track below, and there were couches and sitting areas that faced various exhibits on the vast walls that ringed the gallery.

Bryan Daughtry and another man were seated facing each other in brown leather armchairs. Daughtry stood to reach for Chapman’s hand.

“Let me guess,” Mike said, looking at two yellow columns positioned next to each other and representing some sort of sculpture. “ The Cat in the Hat?”

“Shall I read to you from our brochure, Detective? ‘A minimal freestanding work, this kinetic fiberglass piece conveys a charming, vertiginous uncertainty.’ Like it? Or do you prefer the one behind me? A very creative new fellow-uses beeswax, hazelnut pollen, marble, and rice to make sculptures, as we say, ‘of mute yet implacable force.’ ”

“Come to think of it, my apartment looks fine with a couple of NFL posters, a slightly used baseball signed by Bernie Williams, and an eight-by-ten glossy of Tina Turner that Miss Cooper gave me. Your stuff makes me wanna puke.”

“Shall we go back up to my office?” Daughtry asked.

Mercer and I started to follow him. Mike stretched out his arm to Daughtry’s companion, who remained seated as I started to walk away.

“Hi. Sorry to break this up. I’m Mike Chapman. Homicide. You are…?”

The attractive dark-haired man, who I guessed to be about forty years old, stood up and smiled, returning the handshake. “I’m Frank Wrenley. How do you do?”

“Well, well, well-Mr. Wrenley. And how do you do? Tell you what-c’mon upstairs with us. I got a few questions for you when we’re done with Mr. Daughtry.”

“Of course. I assumed you’d want to talk to me about Deni. I’m happy to try to help.”

Mercer whispered to me as we walked to the narrow staircase, “You and Mike go at Daughtry. I’ll baby-sit Wrenley till you’re done, so he doesn’t make any calls while he’s waiting. This is a rare opportunity to get him when he wasn’t expecting us.”

Mike and I settled into the dealer’s office with him. “Like I told you, we got a warrant to go through your gallery and warehouse. A team of detectives will be here shortly to do that. You can make this real easy on yourself if you wanna give us most of what we ask for, which are Deni’s business records and belongings, access to the contents of Omar’s locker, and things like-well, look at the papers for yourself.

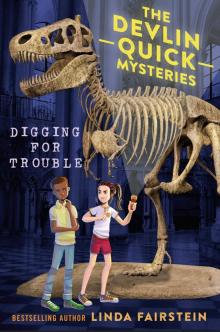

Digging For Trouble

Digging For Trouble Blood Oath

Blood Oath Likely To Die

Likely To Die Bad blood

Bad blood Cold Hit

Cold Hit Entombed

Entombed Final Jeopardy

Final Jeopardy Lethal Legacy

Lethal Legacy Killer Look

Killer Look Secrets from the Deep

Secrets from the Deep The DeadHouse

The DeadHouse Alex Cooper 01 - Final Jeopardy

Alex Cooper 01 - Final Jeopardy Deadfall

Deadfall Hell Gate

Hell Gate Terminal City

Terminal City The Bone Vault

The Bone Vault Silent Mercy

Silent Mercy Night Watch

Night Watch Death Dance

Death Dance Terminal City (Alex Cooper)

Terminal City (Alex Cooper) The Kills

The Kills Devil's Bridge

Devil's Bridge Into the Lion's Den

Into the Lion's Den