- Home

- Linda Fairstein

Cold Hit Page 10

Cold Hit Read online

Page 10

“You think Deni Caxton knew that when she hired him?” I asked.

“Let’s hope we’re about to find out. Daughtry returned my call late last night. He’s waiting for us at the downtown gallery. Ready for this?”

Mike and I left our cars parked near the rail yards and rode down to Twenty-second Street between Tenth and Eleventh Avenues in Mercer’s department car. I had never met Bryan Daughtry but knew well the story of his involvement in a murder in Westchester County almost ten years earlier, even though he had never been charged or prosecuted.

In the late eighties Daughtry had a gallery in the Fuller Building, where Lowell Caxton still maintained an upscale presence. Daughtry was forty years old at the time and had worked his way up quite rapidly from apprenticing with another successful dealer to owning his own business, once he became the personal business associate of the wealthy Japanese collector Yoshio Tsukamoto.

Daughtry was buying and selling major works-Jackson Pollocks and Franz Klines-and living a lifestyle that matched his newfound ability to afford it. A town house in the east sixties and a grand Victorian country place south of the highway in East Hampton. He was intensely private about his personal relationships, but rumor had it that he preferred teenaged girls-young, lean, fond of drugs, and dressed in leather.

By 1992 his professional life seemed to be unraveling just as quickly as it had taken off. Creditors had trouble collecting money from him-even small amounts-and auction houses as well as other prominent dealers began to sue because of misrepresentations Daughtry had made about ownership of some of the works he sold. Then the IRS piled in after a disgruntled accountant whom Daughtry had fired reported that Daughtry had withheld tax payments on more than $ 5 million of income. Informants told the Feds that he was buying almost fifty grams of cocaine a week, at $ 100 a gram. His lawyers were working on a deal to get him out of his legal problems.

And then, the body of a fifteen-year-old Swedish girl, a would-be model, was found in a wooded area surrounded by enormous private estates in a suburban town north of Manhattan. The bird-watchers who stumbled on the carcass were stunned to find that the only part of the remains that had not been consumed by rodents was the stunning head of the child, her faded blue eyes staring out from a black leather mask that tightly covered her skull.

I reminded Mike and Mercer of the rest of the story. Posters of Ilse Lunen had been plastered all over the Village, where she had last been seen at a leather bar, one frequented by Daughtry and his crowd. Although no one had placed the dealer there the evening of the girl’s disappearance, his closest personal assistant, Bertrand Gloster, had been at the bar for hours and was known to pimp for his boss when Daughtry was too wrecked to appear on his own.

In fact, it was rare for Bryan to come on to his subjects faceto-face. His preferred mode of pickup was to sit in a private room on the third floor of the building in which Cuir de Russie (“Russian leather”), as the bar was called, was situated. He’d stare out the window for hours, doing an occasional line of coke. When he saw a girl who was young and nubile enough standing on the sidewalk for a chat with a friend or a smoke, he would call the number of the pay phone outside the bar, talk to his target, and invite her up to the owner’s lair.

Long after the death of the Lunen girl, people in the art world told stories of visiting Daughtry in his office, where he often had sex toys casually displayed on his desk and cabinet tops-handcuffs, collars, studded bands, and even leather masks like the one found on the corpse. In those same encounters he would refer to the ever-subservient Bertrand as “my executioner,” the enforcer who had been brought in to serve as a bodyguard against the rough characters Daughtry encountered in this underside of his life. No one took his words seriously at the time.

Also later, acquaintances admitted hearing stories of the sadomasochistic games that Bryan and his pals had favored, wild evenings of drugs and sex, complete with whips and chains, during which Daughtry increasingly lost his self-control.

Bertrand Gloster was picked up within days of the discovery of Ilse Lunen’s body. He had once been employed as a caretaker on one of the neighboring estates, and his borderline intelligence level made him an easy subject for police interrogators. He admitted killing the young girl, who had gingerly agreed to participate in the S amp;M activities in return for Daughtry’s promise of an airline ticket home to Sweden.

In Gloster’s chilling confession, he described Ilse Lunen putting on the leather mask and zipping its mouthpiece shut before Daughtry handcuffed her behind her back and directed her to kneel behind a large boulder in the woods. Then, Gloster said, the already floating art dealer snorted a few more lines and leaned over to whisper to Ilse, “You’ll be going home, all right-in a wooden box,” before he ordered Gloster to shoot her in the back of the head.

“End of story?” Chapman asked.

“Not exactly. Gloster’s doing twenty-five to life for murder, and the Westchester D.A. has never been able to nail Daughtry.” The testimony of an accomplice has to be corroborated by some other evidence-it’s not sufficient in and of itself to charge the coconspirator with the crime of murder. “There has never been a single other thing to link Daughtry to the child’s death.”

“So this friggin’ lunatic did eighteen months for tax evasion and now he’s back in business like he’s a normal guy, right? Man, I’d like just five minutes alone with him while you wait in the car. Whaddaya think, Coop? No loss to society, I promise.”

Mercer parked in front of Galleria Caxton Due, the newest Chelsea outpost, which Deni and Bryan had just been setting up for a fall premiere at the time of her death. It was too early in the day for the galleries to be open, so there were few other cars and little pedestrian activity on the street.

Mike paused briefly to read the sign that was posted below the bell: “ Service entrance in rear on Twenty-third Street. Hope that doesn’t mean us.”

The front door was unlocked, so Mike pushed it open and we followed him in. The cavernous first-floor space of the former auto repair shop had been completely whitewashed and gutted of all signs of its earlier life. New Age music played on speakers tucked up high in corners of the room.

“Guess they’re not set up for the exhibition yet.”

“You’re about to step on a masterpiece, Mikey. Read the sign.” I pointed to a piece of gray string, about twelve feet long, that extended out from the wall to form a triangle and was tacked to a point on the floor near my left shoe. He ignored me, looking around, instead, at similar strands of colorless yarn spread across sections of the gallery like giant cat’s-cradle forms. I called out the words written on the placard describing the display: “In these string sculptures, the space takes on an incorporeal palpability, concentrating on the planar or volumetric components. Illusion and fact are interwoven, with overlapping linear trajectories.”

“This is art?” Mike responded. “You think some horse’s ass is going pay money for these things? I never saw anything so useless in my entire life.”

Bryan Daughtry’s voice called down to us from a high balcony area off to the side of the airy room. “Don’t be so quick to declare this one the most absurd, Detective. There are several more floors above you might like to see. Why don’t you take the lift up here to my office?”

“Can I make it up there without hanging myself on any of this string crap you call art?” Mike said to Daughtry, rolling his eyes at the bizarre exhibit of yarn sculptures that stretched across the mostly bare space on the ground floor. Then he turned to me. “Let’s head up, blondie. Maybe if I dangle my handcuffs in front of him he’ll get a hard-on. You’re certainly much too old for his taste.”

There was a small lift in the far corner of the wide room. When the doors of the elevator opened on the sixth floor, I was struck in the eye by a blaze of light. The southern exposure of the building was a wall of glass, which let the bright midday sun flood into this most unexpected setting.

From this point, with no tall buildings

in the immediate area, I could see over the rooftops of nearby galleries and garages and out to the Hudson River, which curved in toward the east just a few blocks below us.

The most striking surprise was that about three floors beneath where we stood, running from the north end to the south side of the airy atrium, was an actual stretch of railroad track. It was heavy, thick, covered with rust, and overgrown with weeds.

I stared down at it. “Is that real?”

Chapman was rapt. “I wish my old man could see this. Sure it’s real. Look,” he said, pointing to an opening where the track ran out of the glass-sided building and across the street, directly into a warehouse facing the Galleria Caxton Due.

I leaned against the railing to see that in similar fashion, the grass-filled ties also ran back out of the converted garage, crossing over the double width of Twenty-third Street and rolling on between two buildings on its north corner.

“What is it?” Mercer asked.

“The old Hi-Line Railroad. Another Hell’s Kitchen special. When they raised the tracks off Death Avenue north of the rail yards, they still needed trains to get down to the meat markets in the Fourteenth Street area. So, south of Thirtieth Street, this became the elevated line. Haven’t you ever noticed the old tracks?”

Mercer and I looked at Mike blankly and shook our heads.

“Just drive uptown on Tenth Avenue and look to your left. The air rights over the railroad tracks were sold off, so all these warehouses were allowed to build above and surrounding the actual path of the Hi-Line. Between every block in the twenties and even below that, till you hit the old Gansevoort Market, you can see the great tracks right from the street.”

Daughtry stepped out of his office, on the southwest corner of the floor, and looked across at us. “Amazing space, isn’t it? We’re the only gallery in the city smart enough to incorporate this bit of history into our design. Glad you appreciate that much.”

He invited us into his chilled office, and despite the temperature in the climate-controlled gallery, I was surprised to see that beads of sweat were pooled on Daughtry’s forehead. He repeatedly dabbed at the streaks running down the side of his neck.

Mike, Mercer, and I introduced ourselves, and he invited us to sit opposite his desk. There were no signs of his former indiscretions here, and although he resembled the photos I had seen in the press during the Gloster trial, Daughtry was paunchier now, and jowls had replaced the even line of his pointed chin.

“I’m sure you know all about my background, Detective,” he began tentatively, as his eyes darted back and forth between us, trying to measure our level of hostility or the extent of our familiarity with his past. His fingers trembled when they were at rest on the desktop, so he kept wiping at his head and neck, even before it was necessary. “But you need to know that I adored Deni Caxton, and I’ll be glad to help you in any way that I can.”

Chapman was unmoved by Daughtry’s effort to set a cooperative tone, so I sat back quietly, like a guest privileged to be at the interrogation but not encouraged to participate. Mike was aware of his witness’s vulnerability, so, in contrast to his meeting with Lowell Caxton, he knew he could control the conversation.

Mike let Daughtry think that if he bared his soul about the tax fraud matter, we’d get off the old case and move on to the mystery of Deni’s death. It seemed to calm him to tell us what we already knew about the tax matter, as though we would think better of him for admitting his wrongdoing aloud.

Then Mike moved his chair directly across from his target. “Now, Bryan,” he said, knowing the use of his first name would bring Daughtry down one more notch, “tell us about her. ”

Daughtry seemed relieved to be off the subject of himself and onto his friend. “Oh, Deni. She’s the only reason I’m still in business today, after getting out of-”

“No, no, no, Bryan. Not Deni. I want to know about the girl -about Ilse Lunen.”

The moisture gathered again on his pasty skin, and now he looked from me to Mercer and back again, hoping one of us would intercede with Chapman and call him off.

“I had nothing, nothing to do with that girl, Detective. I’ve never been charged with any crime. That sick little bastard should have been strung up and-”

“And stringing you up would probably have given you more pleasure than any pervert like you deserves, Bryan. Just keep in mind that there’s no statute of limitations on murder. You play with us on this case, you tell me even one little white lie about you or Denise Caxton or Omar Sheffield, and-”

“Omar? What does he have to do with any of this?”

The collar of his hunter green sport shirt was soaked through, and the underarms matched it. His surprise about Sheffield seemed genuine to me.

Chapman continued. “The slightest misstep with us, and I’ll go to the ends of the earth to find the nails for your coffin, the evidence that’ll stick you in a jail cell right next door to Bertrand Gloster. So, now-you tell me, Bryan. What’s this operation all about? And sit on your hands while you’re at it- you’re making me crazy with all your mopping and dabbing. Take a shower after I leave-you need it anyway.”

Bryan responded like a three-year-old child and literally put his hands under his thighs. He explained how he and Deni had met in 1990, when both of them had galleries in the Fuller Building. They discovered their similarities early on-both from poor families and with invented histories, each with an untrained eye but great instincts. Deni and Bryan delighted in the big sale to a famous client, and both would do almost anything-testing the boundaries in a fairly sedate business-to stumble upon a sleeper, a lost masterpiece that had suddenly come back on the market, and then find a Streisand or a Nicholson to buy it.

“Don’t forget the candy. You still sniffing, Bryan?”

“Not really.”

“No such thing as ‘not really’ when it comes to cocaine addiction. You and Deni had that in common, too, didn’t you?”

“May I wipe my mouth, Detective?” Chapman nodded and Daughtry lifted one of his hands and wiped his face and neck with the sleeve of his shirt. “We got high together occasionally.”

“Who’s your source?”

“Actually, Deni was. With my felony conviction I couldn’t take chances buying off the street. I relied on my-well- friends to give me coke. Artists, dealers, even the guys who work in the warehouse. There’s no shortage of the white stuff on the streets. You know that.”

Chapman stood and looked out through the glass wall of Daughtry’s office, down over the tracks to the string-lined display that we had seen on entering. “Did Denise really go for this garbage? I mean, you’ve seen the paintings in her home, and in Lowell’s gallery, haven’t you? They’ve got an amazing collection.”

“Detective, van Gogh only sold five of his paintings in his lifetime. Relatively speaking, merely a handful of artists have ever been recognized by their contemporaries. Deni wanted to get in on the next wave, pick the giants of the future, take some chances. What Lowell does with his collection of masters takes no brains at all, no imagination. Just money.”

“Let’s talk about your business.”

“It’s Deni’s business, not mine. I’ve put some money into it, but she couldn’t risk attaching my name to a venture like this. Too many people seem to remember too much.”

“D’you know she was having problems? Legal ones?”

“Of course I did.” Daughtry looked down at his desk. “I mentioned van Gogh a moment ago. I’m sure you knew about the controversy over Vase with Eight Sunflowers. ”

“Let’s say we know our version of it,” Mike bluffed. “Why don’t you tell us yours?”

“There’s a bit of a storm in the market these days. Vincent van Gogh only painted during the last ten years of his life. He’s been credited with completing 879 oils, 1, 245 drawings, and a single etching.” Daughtry was talking to me now, as though Mercer and Mike wouldn’t be able to understand the story.

I glared back at him. “Talk

to the detectives, Mr. Daughtry. They’re much better at this work than I am. They’re really quite intelligent.”

“The brouhaha is that a great many experts now believe that some of the most famous paintings, and even the one etching, are fakes. In fact, they suspect that many of van Gogh’s contemporaries created them and others passed them off as the real thing. Since his work is fetching higher prices than almost anyone else’s, it’s a rather hot debate these days.”

“And Deni?”

“Well, Deni recently sold Eight Sunflowers to a client in Japan. I don’t know his name offhand, but it’s a matter of public record. He’s now made a claim with the United States government-”

I broke in. “I don’t get it. There are supposedly fake van Goghs everywhere from the Musée d’Orsay to the Metropolitan.”

“Yes, Ms. Cooper, but the gentleman’s claim is that Deni sold it after she had sent it to Amsterdam to be authenticated by the curators there, and after they’d told her its value was questionable.”

“So, after she’d been told it was a copy?”

“An opinion she fought vigorously with the Dutch Ministry of the Arts.”

“But rather than waiting for the outcome,” Chapman said, “she stiffed the client anyway. How much?”

“Four-point-six million.”

Chapman let out a whistle. “Not a bad day’s work, Bryan. What’s your cut of that? And what do you know about the bidrigging investigation the Feds are doing?”

Daughtry was shaking his head. “I didn’t have a piece of the van Gogh. I’m only involved in buying the contemporary works.”

Chapman was pacing the small room, looking through the glass panel at the space below. “Phew. You musta had that leather mask wrapped too tight around your brain. This junk’ll never bring you a nickel.”

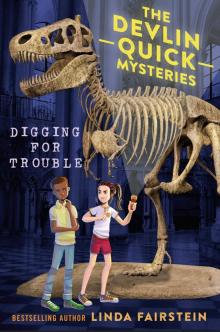

Digging For Trouble

Digging For Trouble Blood Oath

Blood Oath Likely To Die

Likely To Die Bad blood

Bad blood Cold Hit

Cold Hit Entombed

Entombed Final Jeopardy

Final Jeopardy Lethal Legacy

Lethal Legacy Killer Look

Killer Look Secrets from the Deep

Secrets from the Deep The DeadHouse

The DeadHouse Alex Cooper 01 - Final Jeopardy

Alex Cooper 01 - Final Jeopardy Deadfall

Deadfall Hell Gate

Hell Gate Terminal City

Terminal City The Bone Vault

The Bone Vault Silent Mercy

Silent Mercy Night Watch

Night Watch Death Dance

Death Dance Terminal City (Alex Cooper)

Terminal City (Alex Cooper) The Kills

The Kills Devil's Bridge

Devil's Bridge Into the Lion's Den

Into the Lion's Den